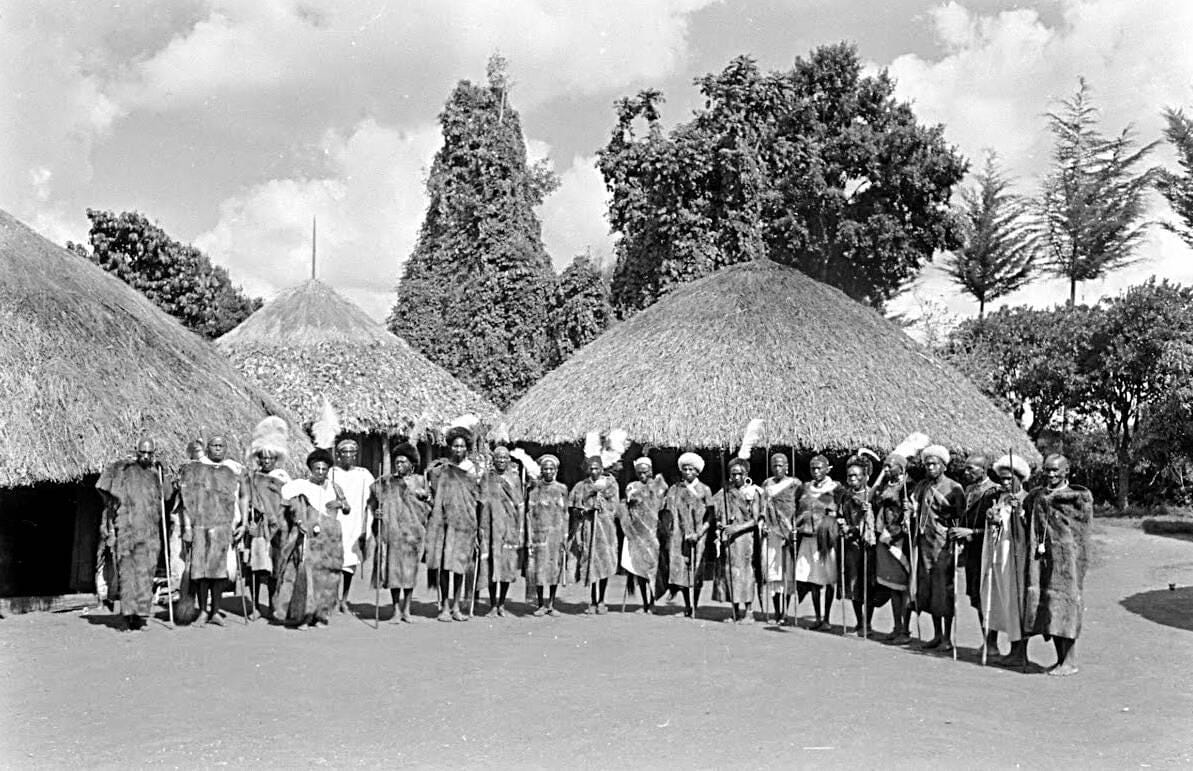

The Gikuyu Marriage System and How It Works

Marriage helped maintain the cohesion of Gikuyu society and enforce conformity to the kinship system and the tribal organization.

Marriage and its obligations occupied a significant position in Gikuyu Culture. The Gikuyu system of courtship was based on mutual love and sexual instinct between individuals; hence polygamy was allowed. The tribal custom required that a married couple had to have at least four children: two male and two female: the 1st female and 1st male children perpetuated the existence of the man’s father and mother. In contrast, the 2nd male and 2nd female children perpetuated the existence of the woman’s parents.

Marriage as a Source of a Higher Status in Gikuyu Culture

Rearing of a family brought with it a rise in social status. On the other hand, a childless marriage was considered a failure. Marriage helped maintain the cohesion of Gikuyu society and enforce conformity to the kinship system and the tribal organization. The validity of marriage and the social position of women in the community was determined by the fulfillment of communal duties regulated by marriage custom.

Choice Of Mate

Both genders were free to choose their mates. From earliest infancy, there was close social intercourse between the sexes which allowed them to know and grow fond of each other for a considerable time before courtship began.

The Stages of Marriage in the Gikuyu Marriage System

The following were the stages and their steps;

The First Stage

When a boy fell in love with a girl, he discussed the matter with his two best friends of his age group. They would pay a visit to the girl’s home whereby they would enter the mother’s hut, and both the girl and her mother would exchange greetings with them. The mother would offer them refreshments and leave immediately. One of the boys would start the conversation with the aim of the visit as the main objective of the conversation.

The girl would at once detect their mission and inquire about the culprit of the mission. One of the boys would point out to the friend who was in love with the girl. At this point, the girl had the right to accept or refuse the possible future husband. If she accepted him, she would tell them to go back and come back at a later date. Alternatively, if she refused him, she would send them away. Normally two or three visits of this kind took place where-after the girl informed the boy that the ceremonial part of their mission was a matter of her parents and referred them to talk to her parents.

The Second Stage (‘Njohi ya Njurio’)

If accepted, the lover would go home and give their parents a report. ‘Njohi ya Njurio’ (beer for asking for the girl’s hand) was prepared and taken to the girl’s parents. When the two parties met, the girl’s parents would provide food to the visitors first. Then the visitors would state the reason for the visit, usually in proverbs. Parents would call the girl, and after being introduced, she would be asked if she had agreed to be engaged. Since she could not directly answer YES or NO, a small ceremony would take place whereby the girl was sent to fetch a particular horn for beer drinking, fill it with beer and hand it to her father, who, after sipping and spitting, would sprinkle some onto his chest.

He would then hand the horn to his wife, who would follow suit. The horn was filled the second time and handed to the boy’s parents, who followed suit. The girl, in each case, took a sip first as a sign of consent. When this initial ceremony was concluded, and the girl was willing to be engaged, the family invited close friends, and they shared the beer among them. Later the friendly gathering joined in prayer (‘Kurathimithia’), uttering unity and the progress of both families.

[Refer to the previous article on The Roots Of Gikuyu Culture: Gikuyu Worship and Religion to get the “Kurathimithia’ prayer]

The Third Stage

When the boy’s parents returned home, they collected sheep and goats (or cattle if they were rich), which were the first installment of the ‘Ruracio’ (dowry), and the lover drove the cattle to the girl’s homestead, specifically to the girl’s mother’s hut.

Another visit would follow in which ‘Njohi ya Guthugumithiria Mburi’ (beer for blessing goats and sheep) was brought, and the girl consulted as in the first visit. Another installment followed until the number of animals amounted to about thirty or forty. The guests did not necessarily bring beer every time. It was considered ill-luck to bring all ‘Ruracio’ at once, no matter how rich you were.

When the boy’s family sent the amount required for sealing the engagement, a day for the actual engagement was set known as ‘Ngurario’ (Pouring out the blood of unity). In this engagement, all relatives from both parties were called and a big feast was provided, including the slaughtering of a fat sheep (‘Ngoima ya Ngurario’), which had to be sent from the boy’s side specifically for this purpose.

The Significance of Ngurario in the Kikuyu Marriage System

The significance of Ngurario was to:

- Announce publicly that the girl was engaged.

- Provide relatives of both sides with an opportunity of meeting and knowing each other.

- To decide on the quantity (how much), the ‘Ruracio’ would be. The amount varied either from one clan to another or from one district to another.

The fat sheep was of a certain color, either black, white, or brown, symbolically for ritual purposes. Elders sprinkled blood and the contents of the stomach along the gateway and onto the sheep or goats or cattle brought for ‘Ruracio’. This signified that they were purified and protected from all evils and the boy’s parents presented them to the girl’s parents as a sign of good faith.

The Fourth Stage

The family discussed the girl’s maturity after all arrangements were made in regard to the ‘Ruracio.’ A final day was set to sign the marriage contract. On the specified day, all representatives of the two clans were invited whereby they brought with them lots of food and drink for the feast known as ‘Guthinja Ngoima’ (slaughtering the fat sheep). The community sought the girl’s consent, and she led by taking part in slaughtering the first animal. Kidneys of the first sheep were roasted and served to the bride-to-be, who ate them to indicate:

- The engagement still holds.

- The families could proceed with the formality of signing the marriage contract.

After this ceremony, people assembled and took part in the feast followed by a big dance and the singing of songs. There was the presentation of gifts by the boy with his age group to the girl’s mother and the members of her clan. At near sunset and after the visitors had left, The family called women representatives for ‘Gitiro,’ which involved opening the presents while cheering each of them, followed by a dance song, which marked the end of the ‘Ngoima’ ceremony. Only women were involved in the ‘Gitiro’ event.

The Function of the Ngoima Ceremony in the Gikuyu Marriage System

The function of the Ngoima ceremony was to:

- Furnish a public wedding celebration in which all marriage agreements were concluded.

- To emphasize that the girl was betrothed to her fiance, not only by her parents but also by the clan body representative acting collectively.

The Wedding Day in the Gikuyu Marriage System

The boy had to provide himself with a hut and prepare for housekeeping before approaching his mother to ask them to arrange a special day suitable for bringing his wife home. The arrangement was made according to certain propitious days of the moon regarding the clan’s history and traditions. The family met in council, where the day was fixed and kept secret from the girl, thus adding a dramatic effect to the proceedings.

The Snatching of the Bride

On the wedding day, the boy’s female relatives would set out to watch the girl’s movements. The girl was, in a way, snatched away while the women cheered on with songs and dances, and the girl would be crying. A counterfeit fight was staged between the women of both parties where families were large. This provided great entertainment and was followed by a liberal feast at the groom’s homestead.

Entertainment by the Bride: 'Kiriro'

Together with her age group, the bride entertained them with ‘Kiriro’ (weeping songs). It was considered as the age group mourning for the loss of the services of one of them. These mourning songs continued for eight days, where the bride was frequently visited by friends and fellow members of her age group. Physical virginity was enhanced; the boy would ascertain signs that the girl was a virgin, and the girl would show that the boy was physically fit to be a husband.

The Adoption Ceremony

On the eighth day, an adoption ceremony was carried out for the full admittance of the girl into the husband’s family. After the adoption ceremony, a day was fixed for the girl to visit her own parents. She would return in the evening with presents from her parents. These presents were regarded as an act of “warming” the bride’s hut. The marriage ceremony would come to an end at this point.

Read more on the Gikuyu Tribal Organization here

A Summary of the Steps of Marriage in the Gikuyu Culture

In simplified terms, the steps were as follows:

- ‘Njohi ya Njurio.’ This was for the love between the girl and the boy and more so utilized to enhance both parents’ friendship.

- ‘Njohi ya Kariki-ini’. This was for the blessings of the tying of the knots ceremony.

- ‘Mburi Mirongo Kenda Muiyuro.’ Parents’ blessings.

- ‘Mburi Ikumi cia Ugendi’. Blessings from the girl’s father and paternal uncles.

- ‘Mburi Ikumi cia Uihwa’. Blessings from the girl’s maternal uncles.

- ‘Ngoima cia Muhiriga.’ Clan’s blessings to the girl. This included: ‘Ndatha Mburi,’ ‘Thenge ya Kirige,’ ‘Ndurume ya Atumia,’ ‘Kinyuhuro kia Mwengu,’ and ‘Horio.’

- ‘Igongona ria Mburi ya Uira’.

- ‘Igongona ria Ngurario’. These were the marriage rituals.

- ‘Ngoima ya Gucina Ndara.’ This ensured no mistake was made and erased any mistake done during the process.

- ‘Mwati wa Kiria.’ This finalized the process.

The Payment of Dowry in the Gikuyu Marriage System

Dowry was done in four phases, which were:

- ‘Runo.’

- ‘Magongona.’

- ‘Maha.’

- ‘Indo cia Mugambo.’

Life Stages for the Gikuyu Woman and Man in Gikuyu Culture

The Gikuyu woman and man had five stages as follows:

- ‘Kang’ei.’ This was a newly married woman with young children. Her husband was known as ‘Kamatimu.’

- ‘Karegeire.’ A woman entered this stage when the firstborn child underwent circumcision rites. Her husband was known as ‘Kiambi kia Ugotho.’

- ‘Nyakinywa Nini.’ She got to this stage when one of her children got married. The husband was known as ‘Muthuri wa Horio.’

- ‘Nyakinywa Nguru.’ She graduated to this stage when the lastborn got married. The husband was known as ‘Muthuri wa Mataathi.’

- ‘Kiheti.’ This was the final stage where all her children were married. She was either a ‘Cucu’ (grandmother) or a great grand ‘Cucu.’ The husband was called Muthuri wa Maturanguru.’

Basically, women in stages 1,2, 3, and 4 were not allowed to participate in most rituals. Those in stage 5 were allowed in some rituals since their wisdom and experience were unmatched.

The Gikuyu System of Polygamy

A man was free to have as many wives as he could support. Several factors why polygamy was allowed include:

- Love for children.

- All women were supposed to be under a man’s protection hence avoiding prostitution.

- The larger one’s family was, the better it was for him and the tribe.

- To have many male children for economic and political reasons.

- To have many female children to render assistance in the homestead and fulfill their sacred duty of creating and rearing future generations. Female children were looked upon as the connecting link between one generation and another and one clan and another through marriage.

- The fundamental idea that the larger the family, the happier it would be.

- To raise the status quo of a man in the tribal organization’s body.

The first wife was known as ‘Nyakiambi.’ The husband had his own ‘Thingira’ (hut), while each wife had her own hut where she kept her belongings and did her cooking. Each wife was allocated several pieces of land. However, the community observed collective ownership. They collectively did the working of the whole land too. The division and distribution of land were overseen by the head of the family, who was the husband.

The community also ensured the distribution of love. Since the idea of sharing a husband’s love was instilled while girls were growing, this made matters easy when they grew up, and they found it natural to share the love and affection among themselves. To avoid jealousy, each wife was visited by the husband on certain days of the moon.

The Duty of the Wives

Women were and are still essentially the homemakers. Each wife had a special duty in the general affairs of the homestead. She was responsible for looking after her hut, her household utensils, her granary, and her garden. The duty of looking after the husband was shared by all in turns in duties like cleaning his hut and supplying him with firewood, water, and food. This also included watering, feeding, and tending, where necessary, the livestock, including sheep, goats, cattle, calves, and kids.

Each wife provided food for her children. Some went to collect firewood in the forest, while others went to cultivate their gardens. During the daytime, everyone was involved in some activity. Only small children left at home or grown-ups who were involved in home chores such as grinding or beating grain in mortars were not. In the evening, each wife cooked in her own hut apart from the one whose turn was to provide firewood and light fire in the husband’s hut. No cooking was done in the main hut. When food was ready, each wife took the husband’s share to his hut.

Divorce in the Gikuyu Marriage System

Divorce was very rare. However, a husband could divorce his wife on the grounds of:

- Barrenness. However, this could be solved through the adoption of a child or marrying another wife.

- Refusal to render conjugal rights with no reason.

- Practicing witchcraft.

- Being a habitual thief.

- Willful desertion.

- Continuous gross misconduct.

A wife could also divorce the husband on the above grounds apart from no. 6. However, she could also divorce him for:

- Cruelty.

- Ill-treatment.

- Drunkenness.

- Impotence.

The wife had the right to return to her father’s home for protection. In the case of a divorce, where a child had been born, the child was always left with the father. In the case where no child had been born, the husband was allowed to claim half of his ‘Ruracio.’

Compiled from:

- Facing Mount Kenya by Jomo Kenyatta.

- Gikuyu Marriage Simplified by Amos K. Kiriro.

- Kikuyu People by E. H. Mugo.